In a war that saw no shortage of crimes against humanity, the Nanking Massacre was one of the worst. Though it happened 76 years ago, continuing tensions between the Chinese and Japanese governments ensure the atrocity is kept alive for as long as it suits political purposes. No visit to Nánjīng 南京 would be complete without a visit to the Memorial Hall of the Nanjing Massacre 南京大屠杀纪念馆. I showed up at 8:30 on a Saturday morning just as the museum was getting ready to open, and was immediately struck by two things: one, even at that early hour, people were lined up waiting to get in; and, two, there were a lot of small children there. Personally, I wouldn't have exposed my eight-year-old to the strong images on display in the hall, but then it's never too early to inculcate the young.

One thing you will see throughout the museum is the figure 300,000, which according to the Chinese government is the number of victims slaughtered by marauding Japanese troops. The International Military Tribunal for the Far East put the toll at 200,000, while estimates by neutral historians range from 40,000 to over 300,000. The Chinese insist on 300,000, the rigidity of which has the unfortunate and unintended effect of giving massacre deniers in Japan ammunition in their attempt to whitewash the atrocity:

The exhibits are understandably disturbing. The displays begin with the lead-up to the Battle of Nanking, showing the effects of the bloody Battle of Shanghai that preceded the attack on Nanjing, which at that time was the capital of the Republic of China 中華民國:

Some of the men who planned the advance on Nanjing:

Nanjing fell on December 13, 1937:

What followed was six weeks of arson, executions, looting and rape unleashed upon the civilians of Nanjing by Japanese troops, in what must have been a hell on earth for those who couldn't or didn't flee the city as the Japanese forces approached. Young and old, male and female, it seems no one was spared. The displays are graphic, as can be expected:

Westerners living in Nanjing formed a Nanking Safety Zone in an attempt to save Chinese civilians. They were led by John Rabe, a German businessman who was horrified by the events unfolding in the city. The irony was that Rabe was a loyal member of the Nazi party:

The museum goes on to detail what happened to those who perpetrated the massacre following the end of the war. Tribunals were set up by both the Allied powers and the Chinese government to try those responsible for the Rape of Nanking. Among those convicted and executed were Toshiaki Mukai 向井敏明 and Tsuyoshi Noda 野田毅, who were notorious for engaging in a contest to see who would be the first to behead 100 Chinese with swords:

Reactions from the contemporaneous world press over the Nanking Massacre:

The Massacre of Nanking was horrifying, and the exhibition hall does an excellent job of laying out what happened. Where it falls short, however, is in the captioning. Although most of the displays are captioned in English and Japanese as well as Mandarin Chinese, it's clear the exhibits are meant for a Chinese audience. Unlike the atomic bomb museum in Hiroshima 広島 which focuses more on what happened at the moment the bomb was dropped and how its victims suffered afterward, instead of dwelling on who was responsible for the bombing in the first place, the hall in Nanjing makes it constantly clear the "Japanese aggressors" were responsible. This caption below, with its references to "national humiliation" and "patriotic education" makes it evident that more than a simple "No more Nanjings" is at play in the memorial hall:

Upstairs, the museum details the history of Japanese military aggression against China, including the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895, in which Japan and China fought over who would be the dominant power on the Korean peninsula (so much for self-determination for the Korean people - Korea had long been a vassal state of both the Ming and Qing Empires). This display on the Wushe Incident betrays its political prejudices - it's portrayed as a general uprising against Japanese rule rather than the localized incident it actually was, and the Atayal tribesmen who carried out the massacre are not identified as such, being referred to instead as gaoshan 高山 people. Several exhibits referred to Taiwan as having been "returned to the motherland" after the war:

Despite what elements of the far right in Japan may say, Japanese military forces committed unspeakable acts of inhumanity against Chinese, Koreans and many others in East and Southeast Asia. And though the Japanese government has expressed regret and remorse on numerous occasions, and the country has led a peaceful existence since 1945, the vocal actions of an influential minority in Japanese politics help to keep memories from being forgotten and hatreds left behind in the past:

However, it must be noted that memories of wartime atrocities serve important domestic purposes, particularly in China. As social problems arising from China's rapid economic growth present a potential threat to one-party rule, focusing attention on a foreign neighbor deemed to have not sufficiently atoned for the sins of the past serves a way to divert anger and resentment away from the government. And as China pushes its implausible territorial claims in the East China and South China Seas, it needs an enemy for its people to focus on. Hence, the nightly TV dramas showing heroic Chinese battling demonic Japanese invaders and museums such as the one in Nanjing:

It's almost as if the population is being prepared for the eventuality of war one day over, say, the Senkaku Islands 尖閣諸島. If such a scenario does play out, however, whether there or in the islands close to Vietnam or the Philippines, the people may be surprised to learn that they will be regarded as the new invaders, and not as the heroic resistors like those who kept the Imperial Japanese Army 大日本帝国陸軍 bogged down in its own Vietnam-like quagmire at great human and social cost:

The present Chinese government has gambled in placing so much stock on what happened in the past instead of looking toward a future of peaceful coexistence. The Memorial Hall of the Nanjing Massacre is an emotionally draining experience, but one that visitors to Nanjing should make an effort to see. It seems to me, however, that even if the Japanese government were tomorrow to apologize unequivocally to all those who suffered during the years 1931-1945, followed by sufficient compensation payments, the government here would still lay on the "patriotic education". To stop doing so would be too fraught with risks to those in charge:

Whereas the Memorial Hall of the Nanjing Massacre was an unpleasant experience due to the subject matter of the exhibits, my next stop, the Presidential Palace 总统府 was an unpleasant experience due to the sheer number of visitors:

A former palace in Ming-dynasty times that was destroyed during the Taiping Rebellion, the reconstructed building was briefly used as a presidential office by Sun Yat-sen 孙中山 in 1912, and then by the Kuomintang 国民党 between 1927 and 1949. As a result, it's high on the list of places to see in Nanjing by Chinese tourists. It was hard to appreciate the classical and Western touches with so many people pushing and shoving to see what was in the various rooms:

Nicer to appreciate, even in the falling rain, were the classical Ming gardens:

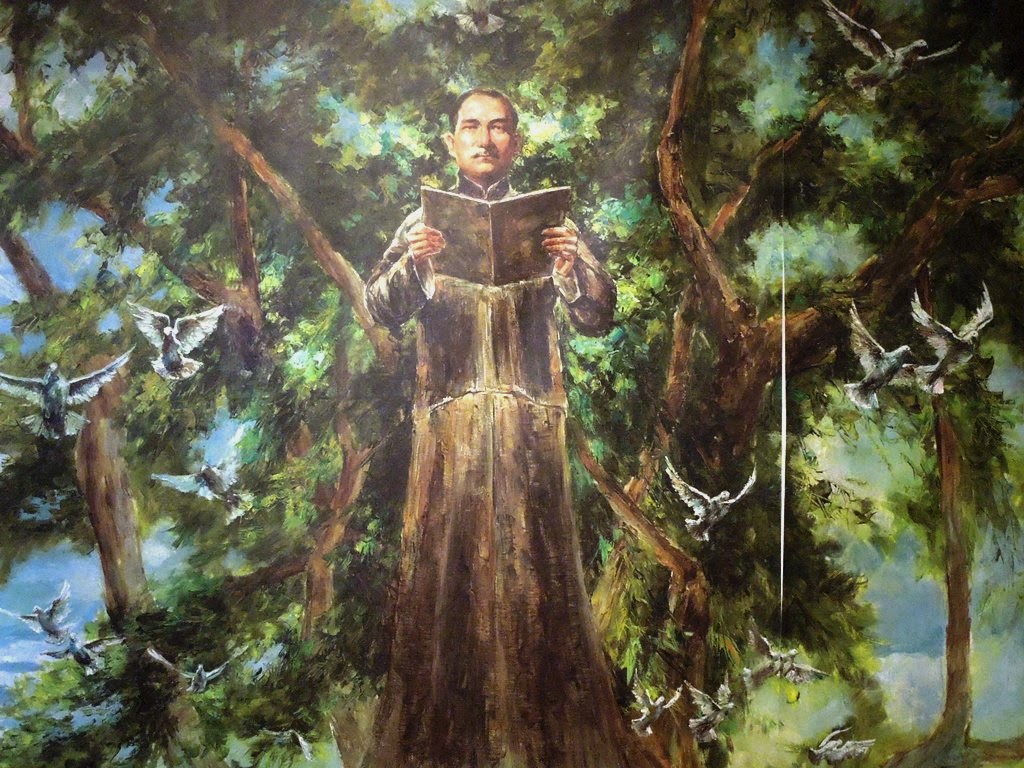

At this point in my China travels, I've seen more historical photographic exhibitions of Chinese historical and political personages than I care to remember. Still, the portraits of Sun Yat-sen on display at the Presidential Palace have reached new heights of ridiculousness, with the ultimate in deification having to be a portrait of him as literally some kind of tree of knowledge:

It was with a great deal of relief that I left the crowds back at the Presidential Palace and returned to modern-day Nanjing. Setting off in search of lunch, it was a long walk down a busy road that was inexplicably lacking in eateries, but where I could've purchased gold jewellery at more than a dozen locations. In the end, I seemingly had no choice but to have a miserable meal at a KFC, only to come across restaurant after restaurant after resuming my walk following lunch. Screw you, Nanjing:

Fortunately, the last sight I visited in Nanjing restored my faith in sightseeing in China. The Zhōnghuá Gate 中华门 is one of the surviving remnants of the original heavily-fortified 13 Ming-dynasty city gates. It's actually four gates, one inside another, and the seven enclosures could hold 3000 soldiers. Visitors can climb up to the top for views of the city:

The story goes that each brick used in the construction of the walls had the name of its place of origin, as well as the names of brick-maker and the person overseeing them:

In any event, climbing the wall was a nice way to end my stay in Nanjing. The city can be safely skipped if you're only going to be visiting China once and your time is limited, but it does make for an interesting excursion from Shànghăi 上海:

The cavernous interior of Nanjing South Railway Station 南京南站:

A bowl of rāmen ラーメン for dinner went a long way toward making up for the debacle that was lunch:

No comments:

Post a Comment